By Annabel Symington

President Yahya Jammeh of The Gambia announced in 2007 that he had discovered the cure for AIDS, whispered to him in a dream by his ancestors. Once again with unwavering confidence in his convictions, the leader of this small West African nation is now pushing its population ‘Back to the land’ in a bid to achieve food self-sufficiency.

His latest incentive involves Africell, the largest mobile provider in The Gambia – text 2131 from your Africell mobile and “Win Free Ploughing plus Free Fertilizing Materials” or “Win 6 Tractors for Free.”

Jammeh’s aim is to prevent The Gambia falling prey to fluctuating food prices of staples like rice. His ‘Back to the land’ policy was launched in 2007 after food prices experienced their sharpest rise in 30 years. The Gambia is one of the smallest and poorest countries in Africa, with over half the population living on less than $1 a day, making them incredibly vulnerable to price fluctuations of staple foods.

In the first ten months of 2009, food prices rose by 9.8 per cent, prompting some to fear a return of the rioting provoked by the 2007-8 rises. The price hikes also cued Jammeh’s latest publicity campaign for his ‘Back to the land’ push.

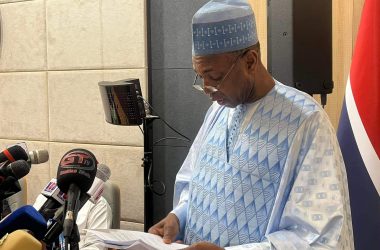

The self proclaimed ‘Farmer President’ claims that he is leading The Gambia back to the land by example. He stages regular public events where he can be seen treading the acres of his farm in the village of Kanilai discussing the virtues of his farming techniques with the local state-owned media. Jammeh’s ‘Back to the land’ initiative appears to stop there though, amounting to little more than rhetoric and photo opportunities.

While Jammeh is promoting mechanisation, as the shiny red tractors of his latest campaign suggest, this is a very short-sighted move in what is a very short-sighted policy. Mechanisation can contribute to increased crop yield – if implemented effectively. But Jammeh has included no provision for maintaining or even running the tractors that are being donated to poor farmers. Of the 14 tractors he recently donated to farmers to boost the ‘Back to the land’ drive, nine were ‘donated’ to his own farms.

And speaking to farmers in The Gambia, it is very clear that tractors are not what they need. Much more fundamental help is required, such as irrigation and fertiliser. Sufficient fertiliser to cover an average crop costs around D650 (£15), which is beyond the reach of most Gambian farmers who don’t even have a stable market to sell their produce. As the government does not regulate the market price of crops, farmers are vulnerable to fluctuating prices and exploitation, a serious barrier to rural development. As a result, farmers often cross the border to Senegal to sell their produce.

Many farmers feel that encouraging people back to the land misses the point; 80 per cent of people in The Gambia already live on the land. The issue is “investment in the land”, said Alieu Jallow, a farmer in the Upper River district.

Many farmers feel that encouraging people back to the land misses the point; 80 per cent of people in The Gambia already live on the land. The issue is “investment in the land”, said Alieu Jallow, a farmer in the Upper River district.

The farmers say there are already enough hands on the land and what they need now is access to fertiliser at affordable prices to help retain and rejuvenate the fertility of the soil. Many have been calling for the government to subsidise fertilizer, but so far their requests have gone unanswered.

Each year infertile soil forces farmers to clear more land for farming. This is leading to land disputes, particularly with the Forestry Department who are currently being instructed by the government to reduce deforestation. Such mixed messages from the government are setting farmers against forestry workers, as each pursues Jammeh’s contradictory orders.

Food self sufficiency vs food security

Jammeh’s ‘Back to the land’ strategy stresses food self-sufficiency over the more immediate need for food security: ensuring that everyone has enough to eat. Too often government policies blur the distinction between the two.

Self-sufficiency in itself is not bad; the problems arise when the rhetoric of self-sufficiency coincides with a growing distrust of markets and trade. Europe’s history of pursuing self-sufficiency with the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) has been extremely wasteful both of money and produce, with crop reserves going bad in storage.

Self-sufficiency at a time of climate change creates further problems. As countries strive for agricultural independence they lock themselves into patterns of production in an attempt to guarantee access to staple foods. But as climate change affects different parts of the world in different ways, trade in food products becomes all the more important to prevent widespread malnutrition and famine.

Jammeh is right to encourage an increase in agricultural productivity, but he needs to back up his rhetoric with policy. During the Green Revolution of the 1960s, staple-crop yields were rising by 3-6 per cent a year. Now they are rising by only 1-2 per cent a year, and in some developing countries, including The Gambia, yields are flat. A stagnant yield coupled with a growing population places The Gambia on the brink of food shortages.

Revolution of the 1960s, staple-crop yields were rising by 3-6 per cent a year. Now they are rising by only 1-2 per cent a year, and in some developing countries, including The Gambia, yields are flat. A stagnant yield coupled with a growing population places The Gambia on the brink of food shortages.

Huw Williams, a British agriculturalist currently travelling in Africa, said that “agriculture in The Gambia has devalued 20 per cent more than Zimbabwe in the last seven years.” This begs the question: How is Jammeh’s ‘Back to the land’ initiative benefiting his population? From 2005 to 2008 The Gambia went from consuming 75 per cent of its own rice, to having to import as large a proportion.

Food self-sufficiency is a false beacon that threatens to stagnate growth as it morphs into protectionism. Developing productive import/export relationships around the world is better for sustained and lasting global development. Any investment in agriculture must be partnered with opening the domestic economy. Pursuing only the former out of distrust of the food markets will undermine any gains from increased investment. And food self-sufficiency must be placed second to production efficiency – that’s the lesson that Jammeh should have learnt from the 2007-08 food price trauma.

This article was initially published by www.thesamosa.co.uk