By Abdoulie John

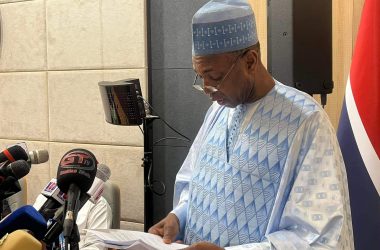

‘‘A very practical man who was ready to fulfil his duty to inform the masses under any government’’ was how Halifa Sallah, a sociologist, politician and journalist, described William Dixon Colley, one of Gambia’s foremost pioneering journalists and civil right activists.

Dixon Colley’s life was the subject of a memorial symposium convened in his honour, which brought together the entire Gambian media fraternity, civil society organizations and pro-democracy activists from all works of life. Held at the Tango Office in Kanifing, Saturday 13 February, 2010, the memorial symposium was organised by the Gambia Press Union (GPU).

By standing for the sacrosanct principles of social justice, freedom of expression and democracy, Dixon Colley made tremendous contribution in the socio-economic development of the Gambia.

A select group of key figures who have had life changing experiences thanks to his influence successively took to the floor to highlight the prominent role the late media icon played in the promotion of democracy in the Gambia and the rest of the continent of Africa.

The initiative of paying tribute to an iconic figure of Gambian journalism, according to Halifa Sallah, constitutes an attempt to provide lessons for the living so that they can draw those lessons and take ownership of them in order to be able to shape a better destiny for themselves.

‘‘Dixon is no longer alive, but he is here with us. He is no longer alive physically, but he is alive in spirit because the contribution he made is still in our memory,” Sallah told the gathering. He went on to say that this confirms that every society has institutional memory and the media is the institutional memory of society. The journalist, he said, is different from the historian. He added that the historian simply writes what has been done while the journalist is not only writing and documenting what has been done, but he is also part of the process of getting it done. That’s where Dixon Colley’s contribution lies.

He went on to say that this confirms that every society has institutional memory and the media is the institutional memory of society. The journalist, he said, is different from the historian. He added that the historian simply writes what has been done while the journalist is not only writing and documenting what has been done, but he is also part of the process of getting it done. That’s where Dixon Colley’s contribution lies.

“To serve a society is a collective responsibility and a society like ours is owned by the people. Each Gambian is sovereign,’’ Sallah said, and he added, ‘‘what lesson then Dixon wanted to drive forward? That’s each individual is capable of doing something, having an impact on society. That is the spirit that each of us should have from this very day. We are all made of spirit knowing that no one has authority to be over us.”

A principled man

The late Dixon Colley dedicated his entire life in using his communication skills and influence to create awareness and provide a platform through The Nation newspaper for citizens to participate actively in the development process of their country.

Re-echoing the words of another outstanding Gambian journalist, Demba Ali Jawo, who worked with Dixon Colley at No 3 Box Bar Road in Banjul, where The Nation Newspaper was located, Madi Jobarteh, in a specially prepared speech, described Dixon Colley as an example in Gambian journalism.

Considered at that time as a source of information for news reporters like Swaebou Conateh and DA Jawo, who established their careers in his honour, Dixon Colley served as an emblematic figure with an irresistible influence in his epoch.

Jawo recalled the Nation Newspaper also serving as meeting point for several left-leaning young ‘‘radicals’’ like Halifa Sallah, among several others, who used to meet there often to exchange ideas about national and international issues.

others, who used to meet there often to exchange ideas about national and international issues.

‘‘Even though since my childhood days I had always harboured the wish to become a journalist, Uncle Dixon had no doubt been the most important catalyst in me realizing such a dream,’’ Jawo said, adding, ‘‘he gave me all the necessary encouragement and support, and he also instilled in me the courage and inclination to call a spade a spade rather than by any other name.”

According to Jawo, the more time he spent with Uncle Dixon, as he was fondly called, the more he admired and respected him for his dedication to journalism and his ‘‘unshakeable principles.’’ He recalled the famous quotation popularly attributed to the late media icon which ‘‘seems to sum up the type of person he was’’ – ‘If what one is saying is right and one strongly believes it is, one should go on saying it up to ones grave.’

Therefore, Jawo went on, for him [Dixon] the question of self-censorship of the truth did not arise. ‘‘He would write anything as long as he was convinced that it was the truth and in the public interest. He therefore no doubt subscribed to the adage; ‘write and damn the consequences.’ I have absolutely no doubt that if Uncle Dixon had been alive and still actively writing in this current atmosphere, he would have been among the first journalists to be sent to jail for what he had written because he would never have shied away from writing the truth, regardless of the consequences,” he said.

The interactions that followed the presentations showed that Dixon Colley, although not well known by the present generation of Gambian journalists, deserves to be elevated to the dignity of the true sons of Africa who have contributed to the emancipation of our continent.

His integrity and outstanding achievements in the field of journalism will certainly continue to inspire his pairs and the incoming generations, as his commitment and vision helped (and will continue to help) to shape Gambian journalism into modernity. In other words, Dixon has really invented our modernity.