“If a man like Deyda Hydara can be murdered for doing his job, then no one can sleep peacefully in his or her bed. Nobody will be spared” -Says Alagi Yorro Jallow.

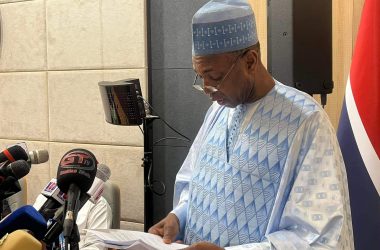

Alagi Yorro Jallow

On February 2, 2003, police in my hometown of Jarra Sankwia in The Gambia during Eid al Adha prayers with my family, arrested and interrogated me about a lead article I had published in my newspaper The Independent.

The story, an all-too-common one in Africa, revealed that my country’s president, Yahya Jammeh, was the owner of a new five-star hotel, the Kairaba Beach hotel and that several of his cronies were among its secret shareholders.

The police demanded that I write a statement disclosing my sources and threatened me with jail if I refused. I did so and was held in solitary confinement. I was stripped naked and kept in a dank cell until my release forty-eight hours later.

This was nothing new. I have been detained and interrogated in The Gambia more than twelve times in the past six years from 1999- 2004.

Government forces have continued to challenge the legality of The Independent, the newspaper I started with a colleague in 1999, and still pressure me to reveal sources for several investigative pieces. This has taken many forms including intimidation, physical attacks, death threats and arson.

Yet none of this can cow me or compromise my independent editorial policy. All I am interested in is publishing factual reports.

I am a journalist – a Gambian journalist – and am prepared for the danger, aches and stress of running a newspaper.

I and a colleague Baba Galleh Jallow established The Independent and served as its managing editor because I was concerned with the long-standing problem of making information available information in The Gambia.

I became particularly concerned with the information vacuum after a change of ownership and editorial position of The Daily Observer in 1999 inevitably narrowed the outlets for independent newsgathering.

Against this backdrop, The Independent was born and took over the mission of informing and educating a growing and increasingly insatiable legion of readers with an emphasis on fearlessly reporting news without taking sides.

With its uncompromising editorial line, the bi-weekly soon became the fastest growing newspaper in terms of readership and popularity, measured by our inability to satisfy the growing demand for the paper.

The Independent had a circulation of 10,000 every Monday and Friday and an estimated readership of over 30,000.

Synonymous with plurality, objectivity and editorial independence, The Independent has fiercely defended its editorial policy.

Operating in a country where the Fourth Estate is usually regarded with disdain by the authorities, the editor and staff recognized the continuous challenge to maintain a presence on the national newsstands.

From the beginning The Independent’s staff has sought to project an objective and honest view of what is happening in The Gambia, and beyond. But from the moment we published our first issue, on July 5, 1999, authorities and their sympathizers have targeted us and attempted to frustrate our publishing efforts.

It became routine for me to receive death threats, which culminated in two arson attacks and injury to staff.

Less than a month after it was granted a license to operate, police raided The Independent’s offices and many of staff were arrested and detained.

The authorities’ excuse was that the paper had not fulfilled all of its obligations to be allowed to operate; this despite the paper’s managing editor being given the green light to start publication by the registrar general of the Attorney General’s chambers, the body responsible for the registration of newspapers.

Because of this initial raid clampdown, the paper ceased publication for two weeks. It was already becoming clear the regime was not prepared to stomach a paper didn’t pander to the whims of those in authority.

The harassment and intimidations continued with unrestrained regularity.

In the months that followed, the managing editor was arrested and detained overnight as authorities attempted to investigate the source of funding for The Independent.

Journalists in The Gambia are frequently arrested and detained by the National Intelligence Agency (NIA).

NIA operatives arbitrarily detain journalists for long periods for often flimsy reasons and the organization has played a large role in The Independent’s troubles from the beginning.

As the authorities and the NIA continued to harass us, no staff member was safe. Even the paper’s female typesetters were bundled to the NIA headquarters in Banjul and detained there for several hours.

The authorities were so hot on the heels of the paper’s editor, that in 2000, they questioned both our nationalities.

In the latter half of the same year, three reporters and I were all detained for different reasons for stories the paper had published. One reporter, Ahhagie Mbye, was detained for eight days, surpassing the 72-hour maximum detention period sanctioned by the constitution.

I have had my own experiences with the NIA, including being held for an article questioning the president’s ownership of the five-star hotel, the Kairaba Beach hotel.

The Independent had reported the distribution of shares for the hotel was unclear, since other information suggested the president held shares in it.

Hardly a week passed without the newspaper being in one form of trouble or another with the authorities or with people who identify with the regime.

I was used to seeing the inside of a jail cell and NIA headquarters. I didn’t like it but was determined not to be intimidated.

Then, on the evening of Oct. 17, 2003, our office was set on fire – for the first time. The newsroom was partly destroyed and the press damaged. A security guard posted at the gate to the paper’s offices was attacked and hit with an iron bar.

A few days prior to the arson attack, I had received a series of death threats via telephone from people unhappy with reportage of issues around key personalities who sided with the regime.

A few months later, on Jan. 13, 2004, I received a letter signed by a group called the ‘Green Boys’. The letter threatened to kill me and destroy The Independent because of its reporting.

They kept their promise. On April 13, 2004, six unidentified attackers illegally entered the office and burned our new printing press.

Hamat Bah, National Assembly member for told the National Assembly he had information that two officers of the National Guard were among those who attacked The Independent, yet to date there has been no investigation.

After we lost our press, The Daily Observer agreed to print The Independent through an informal arrangement. In early May I was notified the arrangement had been terminated. No reason was given.

The Independent was not published from May 6 to July 8, 2004 but has now resumed publication by a skeleton staff in The Gambia and a few determined reporters and editors located elsewhere. Its circulation has dropped almost 50 per cent and it is printed on a smaller sheet by anonymous sources.

I believe other Gambian printing and publishing outlets have refused to print the newspaper on contract because they have either been threatened not to print The Independent or they fear that they or their presses could be attacked as well.

When it began, the Independent had 25 staff members including freelance journalists. But since April 2004, many the Independent’s senior reporters and support staff have fled.

Some of its best journalists sought political asylum in Europe and the United States, where I myself live in exile.

If freedom of the press remains a challenge in The Gambia, so do the economic costs and personal risks of operating a newspaper.

In Dec. 2004, the National Assembly passed an amendment to the Newspaper Act increasing the bond deposited by non-governmental newspaper publishers and managers of broadcasting institutions from US$3,448 to US$17,240.

Immediately afterwards, the Assembly passed amendments to the criminal code broadening the definition of libel and imposed mandatory prison sentences of six months to three years for offenders.

In June 2004, the Assembly amended the criminal code and established the option of a fine between US$2,000 and US$10,000 as an alternative to prison for defamation and sedition and hiked the minimum prison sentence from six months to one year.

The assassination of outspoken senior journalist Deyda Hydara, editor and publisher of The Point newspaper, in Dec. 2004 made it clear the government was desperate to curtail the independent media and would go to any lengths to gag opposition voices.

Hydara, my friend and colleague, was gunned down in his car while driving home from work. No one has been arrested in the case, which police and government have not fully investigated.

If a man like Hydras can be murdered for doing his job, then no one can sleep peacefully in his or her bed. Nobody will be spared.

Today, self-censorship is a real possibility in The Gambia.

People are even more guarded than usual in what they say and write for the public. Hydara’s death has sparked a climate of fear that could lead to fewer voices critical of government.

Families of journalists and independent media workers, even the families of those who operate the printing presses, are now pressuring their loved ones to refrain from overt criticism of the regime and to look for other employment. Even a slight association with the independent media is a dangerous thing.

In the past, President Jammeh and his government have used decrees and laws to harass the independent media and to curtail its freedom to operate. Now they have added murder to their game plan. Anyone who is brave enough to oppose their agenda will not be immune to death or threats of death.

Arson attacks, arbitrary arrests and physical violence will not silence the brave voices of Gambians searching for justice and good governance.

For everyone journalist who is murdered there will come four more prepared to stand up to the thugs who would silence us.