Based on the testimony of the police witnesses at the Truth, Reconciliation & Reparations Commission (TRRC) one could notice their common distinctive position of having prior knowledge of the Gambia National Army’s (GNA) overwhelming strength in terms of lethal weaponry that far outmatched that of their entire forces to stand the soldiers in battle.

Based on the testimony of the police witnesses at the Truth, Reconciliation & Reparations Commission (TRRC) one could notice their common distinctive position of having prior knowledge of the Gambia National Army’s (GNA) overwhelming strength in terms of lethal weaponry that far outmatched that of their entire forces to stand the soldiers in battle.

One after the other, each of them had painstakingly lamented over how the government had disregarded their protest over the massive armament of the GNA by the Nigerians and still expected them to stop the soldiers if they had turned mutinous again.

What I think they should have also added was that the actual commander of their military police wing Lt. Yahya Jammeh and his best men who had always been in the forefront when confronting the army had transferred to the GNA out of among other reasons his dissatisfaction with their paramilitary force’s transformation into an armed wing of the Gambia Police Force.

That said, I also don’t think the officers had any excuse for disregarding the fundamental principle of waging warfare that emphasizes the need to be assured winning a war before starting one in the first place. Signifying that by accepting the orders to fight a war that they were certain of losing was tantamount to obeying an illegal order, another violation of a military dictum that only exposed the troops under command to possible massacre.

So, I beg to ask, what in the world was the police command thinking after having all the vital intelligence before them showing their inadequacy to win the army in battle but still carried out the illegal operation of deploying their men to Denton Bridge for what I could best described as a suicide mission?

We could still interpret it as it had appeared; that the Tactical Support Group (TSG) were merely posing as scarecrows hoping that with divine luck the soldiers would panic and retreat upon seeing them at Denton Bridge and if they don’t but still advance forward they simply surrender and join them, period. You never know, listening to Abu Jeng’s mischaracterization of the fighting zeal of the GNA, a dumb proposition like that could have very well emanated from him.

Nonetheless I still blame them for disregarding every cardinal principle of warfare as taught in military academies or on their poor memories of not remembering their school notes, indicative of their conflicting evidences at the TRRC over what exactly happened in their presence, at the same spot and time at the bridge.

We shouldn’t however rule out adventurism for the glamour of being recognized as heroes. I was one soldier who hated war and have many times been called a coward or a bad soldier. But as far as I am concerned, preventing a war and being identified a coward is far more progressive than waging one for the mere title of being a warrior. I don’t think soldiers or people in general can be trained into being warriors or cowards, circumstances make them so.

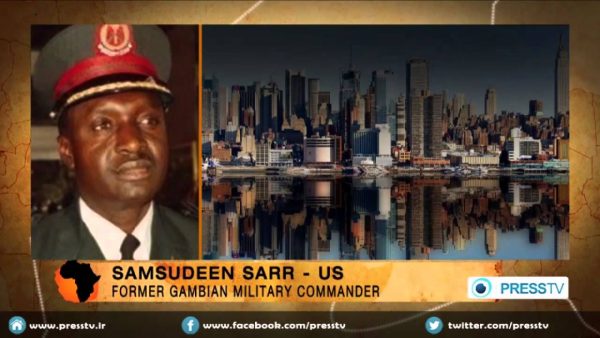

Anyhow, the police DIG factually mentioned at the TRRC how he and I futilely tried to sensitize the PPP government to do something about the national security threat posed by the weapons issue.

Yet to be quite candid, as staff officer at the Ministry of Defence (MOD) for two consecutive years, I don’t think there was another officer from the GNA or police who had raised more concerns about the arms menace than the ADC to the head of state. With the exception of the president and the vice president we had virtually approached every official holding key position at the MOD and at the president’s office drawing their attention to the problem.

Notwithstanding, the police DIG who had always been informed about every development of our efforts, no matter how trivial, had now closed the Denton Bridge, pistol in one hand and a field radio commonly known as walkie-talkie on the other strictly warning me of their determination to fight the GNA if they attempted to cross over to Banjul. He showed genuine frustration and anger against the soldiers.

Seeing how upset he was, I first reminded him of what we had all along been campaigning for; for the government to either distribute the country’s military arsenals equally between the army and the TSG or for them to purchase similar heavy weapons to balance the combat capabilities of the two rival forces. Of course, it was all about deterrence and not waging war at all.

“From the message we received at the State House”, I told him, “that the GNA soldiers had broken into the armoury and are armed with the weapons in stock, you and I know that negotiating with them for peace and preventing an armed conflict makes more sense”.

The DIG like I said had worked closely together with us, i.e., the ADC to the president and I on the weapons dilemma.

At one time on a rare opportunity orchestrated through informal appointment, the ADC and I met the Secretary General and Head of the Civil Service to raise the same concerns about the guns. He acknowledged our unease over the situation but dismissively assured us not to worry too much since the government was in a vigorous bilateral arrangement with the State of Israel to fully equip and train the TSG with better and more sophisticated weapons.

I think the DIG wasthe first person I called at his office after leaving the Secretary General’s office to update him on the response we received.

And in a final attempt in my capacity as the military liaison officer, I formally took an initiative of writing a paper about the situation, further highlighting the lack of serious activity by the GNA by having nothing much to do in the barracks and even recommended the exploration of committing them, if possible, to international peacekeeping missions just to keep them busy. I sent the document to all important officials within the State House.

Before I know it the Permanent Secretary at the office of the president, said to have been the president’s nephew, summoned me to his office and severely told me off for stepping beyond my bounds in trying to advise them on matters that they really didn’t care to hear from me. That if they needed advice they would simply get it from the Nigerian generals and colonels hired in the country to advise them.

The DPS at the MOD who sounded more understanding also invited me to his office to tell me how my action was generally interpreted, as coming from a person seeking promotion or a better position. That was four months before the coup.

I had indeed even made an attempt to quit the army to transfer to the police where I had assumed could provide the D.I.G and I a better chance of working together to get the needed weapons. He was very excited about it and showed total support of my plan. It wasn’t after all possible because I couldn’t agree to their terms of first reducing my captain’s rank in order to be accepted in the police force.

Anyway, reminding the DIG in charge of the Denton Bridge closure of what we both knew about the strength of the forces on the other side seemed to have calmed him down into giving chance to negotiation instead of fighting. In other words, after reasoning with him he showed a better understanding of the situation and the unnecessary trouble of fighting; I was hence allowed to cross the bridge to the other end where I still didn’t know who exactly were there.

He later told me how one of the senior police officers with him was suspicious of my complicity and just wanted me arrested; although in his testimony at the TRRC the DIG tend to have either forgotten about our whole interaction at the bridge or must have consciously omitted it in his statement for personal reasons. But that was the truth, witnessed by his men that day including the senior police officer suspicious of my actions whose name I will not disclose for now. I am in fact carefully avoiding people’s names so as not to offend them.

The DIG’s stance was certainly that of a warrior’s but in my judgment I would rather commend him for his ultimate understanding to avoid a fight than anything else. We didn’t need wars the likes of which in third world countries often translate into everlasting and senseless destruction of human lives and properties.

The first civil war in Liberia was still raging with its ugly consequences. Charles Taylor in 1989 had planned to invade and win the war against the government of President Samuel Doe within a month or less. But due to the fluidity of civil wars and their unintended consequences the horrible carnage continued for eight years causing the death of over 250,000 people mainly civilians with over 2 million of them forced into exile, not to forget the immeasurable destruction of public and private properties in the country.

After three decades of that brutal war with the eruption of a second bout lasting another four years 1999 to 2003 Liberia is still in the process of recovering from its devastating effects. The belligerents who thought they could survive or win were over time all consumed in the violence. Charles Taylor the initiator now sits in a prison where he may never leave alive.

The politically-incited genocidal war in Rwanda wasted the lives of 500,000 to 1,000,000 innocent people between April 7 and July 15, 1994. Images of the mass slaughter civilian men, women and children shown on world televisions and magazines revealing the regrettable excesses of such internal conflicts were still fresh in our minds.

Evidently, conflicts of such nature when started are often usurped not by well-trained soldiers or disciplined police forces but by murderers, psychopaths and criminals turning into religious, ethnic, sectarian, tribal or gang war lords having no conscience and no respect for the Geneva Convention or the Laws of war.

Moreover, those wars in Liberia and Sierra Leone also proved how underage children forcibly conscripted into rebel militias, armed, drugged and indoctrinated by war lords become more vicious and deadly in battle than regular trained professionals.

Similar wars initiated in places like Iraq, Afghanistan, Libya, Syria, and in several African countries all turned out the same. Not winnable by any measure of strength or heroic actions but instead only create one war lord after another who have never been conventionally trained.

In his inaugural speech to the United Nations, the new Secretary General, Antonio Guterres, enjoined all 193 member states, particularly the superpowers to avoid starting wars because they are no longer winnable like in the past when they were fought with guided principles and laws.

So praise be to the TSG in 1994 and kudos to the GNA during the impasse in 2016 together with all their commanders for saving The Gambia from a potential civil war. Trust me you all were enough heroes deserving medals of honour for avoiding war.

However, what I expected to see on the other side of the Denton Bridge on July 22nd 1994 was totally different from what I found after crossing. In the past two army demonstrations in 1990 and 1991, the mutineers were led by non-commissioned officers – corporals for that matter – with no officers involved.

But with this one, there were three GNA officers leading the men. And they were not ordinary officers. The captain whom I had enlisted with in the army the same day in 1986 was the commander of B Company although most of the men I recognized behind them were from C Company. He was the most senior among the officers and at first behaved as if he was in control.

Then there was Lieutenant Yahya Jammeh, the head of the GNA military police unit. He had transferred from the TSG since the arrival of the Nigerians and had just returned from America after successfully completing a military-police-officer training course. I was particularly shocked to see him leading.

As the head of the military police with his past record in the TSG of challenging the GNA soldiers in both of their previous demonstrations, seeing him not stopping them this time but leading them instead finally confirmed to me the seriousness of the rebellion.

Then there was 2 Lt. Edward Singhateh, the sharpest shooter in the GNA, winning that title for two consecutive years. He was among the youngest junior officers in the army, very likable, eloquent and the kind of officer you will want to befriend for his looks and gentle manner. He was a platoon commander in C Company. He was not that cool as I later discovered.

Then to my utter disappointment I saw a very important GNA senior NCO, the second in command of the mortar platoon headed by 2 Lt. Sana Sabally. He was holding an anti-aircraft gun mounted on one of the GNA trucks. Disappointed because he was one of the few men I had asked about the rumoured coup on that Monday 18, July and he denied anything like that happening in the barracks. He even assured me that he will never support a coup and that none could happen without his cooperation. I later learnt that he was forced to join the coup but didn’t survive the November 11, 1994 “counter-coup”. May his soul rest in peace!

I faced the three officers and first asked them what was going on. The captain aggressively pointed his hand gun to my chest and said, “Captain Sarr, this is a coup. This government must go today and you will join us by force whether you like it or not or get arrested.”

He turned around and ordered a soldier to give me a rifle. I told him categorically that I will not join them even if my life had depended on it.

“And I don’t care whether it is a coup or not”, I fired back to the captain, “but with the Americans on their way coming for what they still believe is an on-going exercise, a mistake of shooting or hurting them will have grave repercussions on all of you”.

Up to that moment I couldn’t figure out who was part of the coup or not.

“And mark you”, I continued “they are coming with the latest models of amphibious tanks powerful enough to destroy this whole country.” That’s where I got the nickname amphibious.

I could immediately notice the taming effects of my words on the captain; he turned and looked at the lieutenants as if lost in thoughts and words. The captain, I also later realized was forced to join the troops.

The two lieutenants, now showing that they were in charge, fired back saying that if the Americans tried to stop them they will fight to the last man, but the PPP government must go “today”.

I argued that fighting should be the last resort with the foremost important thing being to find a way of letting the Americans know that the exercise was called off. In that case they will organize an orderly withdrawal of their forces back to their ship.

I also warned them about the reason the criminals and bandits hadn’t yet started looting private and public properties. That the Gambians are still with the belief that the military exercise organized by the GNA and the visiting American troops was the reason the soldiers were in the streets. Shooting could therefore not only get the Americans into the fight but would definitely trigger a nationwide looting spree never factored in the operation.

“How can we let the Americans know Captain Sarr, because no matter what, this government is finished?” retorted a lieutenant.

“Why not go back to the Gambia Radio Station at Mile 7 and make an announcement to that effect?” I suggested.

Going back was no option. They urged me to go to the radio station with a section of the troops and make the announcement for them. We agreed on that.

But before that, I was to go back to the bridge and talk to the TSG to understand that they didn’t want to fight but if forced to, they will.

I also agreed to that and turned back towards the bridge. But while walking back the soldiers armed with RPGs, grenade launchers, heavy machine guns plus their personal AK47 rifles, all followed me closely.

TSG men started emerging out of their hideouts in the mangrove swamps. For the first time I saw Captain Amadou Suwareh and Lt. (Doctor) Binneh Minteh carrying light weapons. The soldiers began confiscating the weapons of the TSG personnel before I could even talk to anyone. Soon the bridge was cleared and the GNA soldiers crossed over. With about 8 to 10 soldiers, a section, including Corporal Njie who later became Sana Sabally’s bodyguard, I joined the State Guard Bus parked at a near distance and headed to Mile 7 Radio Gambia Station for the announcement to warn the Americans and Gambians that a military coup d’état was underway in the country.

What happened at Radio Gambia could be read in the next part.

To be continued.